Abode Feature: Transcending Wounds to Dream of Hope and Healing: An Interview with Hayun Cho

"I was curious about the impulse to notice and appreciate small signs of life, to hold onto imagination." Read on for more about Hayun Cho's thoughts on the Korean diaspora and women in myth.

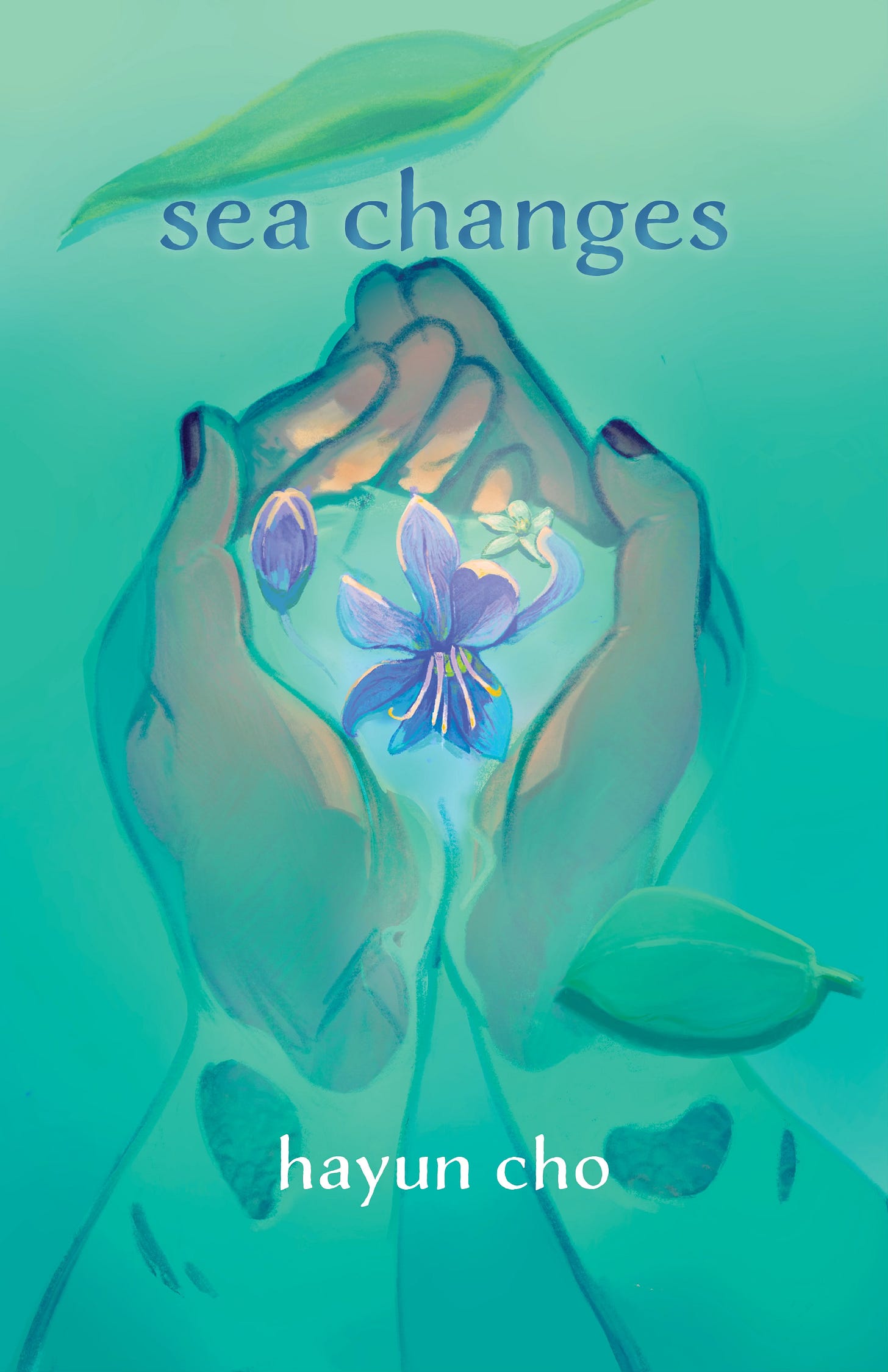

It’s been just over a month since Sea Changes by Hayun Cho has entered the world, and our very own Angela Heiser, Poetry Reader and Publicity Intern at Abode, sat down with the author to get her insight. Sea Changes is a hybrid collection that weaves together theories of survival and transformation in the face of negotiating rage, grief, pleasure, kinship, and the Korean diaspora. It is the seventh chapbook in Abode's 2024-2025 lineup and is officially available here!

Hayun Cho is an Assistant Professor of East Asian Languages and Cultures at the University of Notre Dame. She researches feminist and queer theory, as well as the role of emotion in South Korean film and literature. Both her scholarly and creative work interrogate gender and cultural norms. Her poetry has been featured in The Rumpus, The Margins, Cream City Review and nominated for a Pushcart Prize. I had the opportunity to ask author Hayun Cho about the inspiration behind and creative process that shaped her debut hybrid chapbook.

Cho excels at crafting searingly strong biting endings in this collection. Her work deftly incorporates the quotidian and the mythical to elevate contemplations of identity, self, and other within the context of womanhood in the Korean diaspora. Choosing apples at the Korean grocery store, chopping vegetables around the kitchen table. Cho grapples with the weight of all we inherit from our foremothers–emotionally and otherwise. And questions whether it is really ours to carry through this world?

Building up to the catharsis, her poems explore rich gifts of nature in the form of jasmine, cherries, rice, but also forests and the titular sea. Changing seasons provide insight into the range of emotional journeys and transformations navigated in these pages. Cho reflects on the role of her foremothers and her own expected role, in a series of poems around the kitchen table, to honor the repressed rage, sit with tangible melancholy and loneliness, and act on the urge to rebel that these women were forced to bury deep within or hand down to her.

The intergenerational emotional inheritance is palpable in the way seismic activity is felt along fault lines. Navigating the fault lines with aplomb, Cho walks through decades of fraught struggles to meet social expectations while maintaining female agency. Not one to balk at a challenge, she experiments with form and typography in this cunningly erudite portrayal of girl-and womanhood in a storm of culture, language and familial history. Out of the decades of collected wounds, Cho nonetheless deftly manifests a persistent hope beneath the surface.

Sea Changes draws on the natural world in a mystical way. How did your work arrive at these themes? What role has the power of the natural world had in inspiring your work?

Many of the pieces in Sea Changes were inspired from ruminations in the lush green of Southern California. I learned a lot about resilience observing plant life. Sometimes I would think a rose bush on my street had died, but the blooms would return just when I had accepted its fate. I was curious about the impulse to notice and appreciate small signs of life, to hold onto imagination and shift one’s perspective even when the world feels terrifying.

Who or what influenced you when writing Sea Changes?

Writers such as Audre Lorde, Alice Walker, Julietta Singh, and Sara Ahmed greatly influenced the way I approach writing as a mode of critique, speculation, and more broadly contemplating one’s position in the world, and what to do with that. Embracing the intensity rooted in creative practice, as emotional as it is intellectual, has been life-changing for me. My family and my friendships also inspire me, as well as my research which examines emotion as feminist knowledge in literature and film. Sea Changes was written during a period when some of my elders were ill, and I was reckoning with what it means to inherit strength and pain from other women. I was also finishing graduate school. During this intense time, writing became a tool to articulate what was happening and what was ultimately changing. I wrote Sea Changes mostly in solitude, so it is meaningful if not strange to share it with an audience.

Do you have recommendations for other writers who discuss the Korean diaspora that we should be reading and/or works in translation?

I love Theresa Hak Kyung Cha, Franny Choi, Suji Kwock Kim, Alexander Chee, Emily Jungmin Yoon, and Michelle Zauner, among many others. I always return to Cha’s Dictee. It remakes the English language, in my opinion, and is one of the books that made me want to be a writer. I would recommend Choi’s The World Keeps Ending, and the World Goes On which beautifully addresses the relationship between political despair and possibility. Kim’s Notes from the Divided Country confronts historical memory across generations and lingers in gorgeous metaphors such as the onion (you’ll know when you read it).

What advice do you have for other writers spanning two cultures?

There is no single origin point, destination, or set of useful definitions of the Korean diaspora in my writing. Sea Changes confronts the messy, unruly hybridity of diaspora through embodied acts of thinking, feeling, and writing. I am sure everyone approaches writing from a space of diaspora differently. I start with the emotions that arise from an encounter, detail, or memory, and go from there. I often write because I need some sort of emotional catharsis or because the languages and texts around me are not adequate to express what I want to express. It feels important to recognize that lived experience can be a formidable archive. Something I’ve found helpful recently is to accept when I don’t write anything I like. Sometimes a stretch of awkward writing or even silence is necessary to the vision, and the vision always changes.

You draw on myth: Scylla and Persephone appear in this work. What is the significance for you?

I was always fascinated by women of myth who were associated with ruin or misfortune. They seemed very powerful to me in their embodiment of the monstrous and the taboo. As a young reader who loved mythology, I sympathized with these women because I believed they deserved better and wanted to know more about their interiority. I wanted to honor that informal education or mode of thinking by placing it in conversation with contemporary, everyday intimacies.

When you are not writing or teaching, what do you enjoy in your free time?

I enjoy going on long walks, running, reading, watching movies, and cooking.

Sea Changes is now available for purchase. Grab your copy here!

Angela Heiser is a Poetry Reader and Publicity Intern here at Abode. Her work appears or is forthcoming in Arcana Poetry Press, Spark to Flame, Gigantic Tentacles, Carolina Muse, The Poetry Lighthouse, and The Red Mud Review. Her poem 'Cornhusker' was awarded the Poetry Genre Winner for the 2024-2025 issue of The Red Mud Review. She is an alum of Writers in Paradise and reads for Abode Press, Wildscape, and Libre Lit. Find her on instagram @angelacheiser.